References:

1. Rozel, J.S., Jain, A., Mulvey, E.P., Roth, L.H. Psychiatric Assessment of Violence. Chapter, The Wiley Handbook of Violence and Aggression, Peter Sturmey (Editor in Chief) 2017, Wiley Publishing.

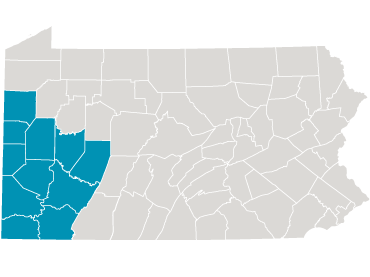

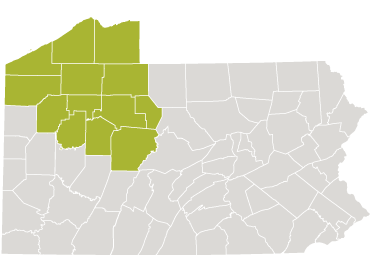

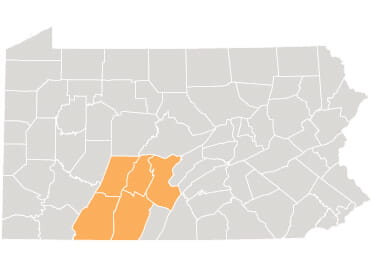

1. Program Description: resolve Crisis Services

Available from Loren Roth MD - Room 604 UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital, Pittsburgh, Pa. 15213

Read the Full Podcast Transcript

Transcript by Rev.com

Dr. Roth: This podcast is for informational and educational purposes only and is not to be

considered medical or behavioral advice for any particular patient. Clinicians must rely

on their own informed clinical judgments when making recommendations for their

patients. Patients in need of medical or behavioral advice should consult their personal

health care provider.

Dr. Roth: Good day, and welcome to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Western

Psychiatric Hospital podcast series. I am Dr. Loren Roth, distinguished professor and a

senior psychiatrist at the hospital. This podcast series presents innovative research and

patient-centered programs at the cutting edge of psychiatry and the behavioral

sciences, of special interest to diverse professionals and the interested public. Our

hospital and clinics are the Behavioral Health Psychiatric Division of the University of

Pittsburgh Medical Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The hospital houses the wideranging missions -- clinical, educational, and research -- of this UPMC specialty hospital

and the nationally known Department of Psychiatry of the University of Pittsburgh

School of Medicine. My guest today is Dr. Jack Rozel. Today we are discussing

emergency psychiatry and crisis intervention, with special emphasis upon a unique

Pittsburgh organization, which has its own location and an interprofessional staff. This is

the resolve Crisis Services. This is an arm and special program of UPMC Western

Psychiatric Hospital. It is fiscally supported as a public service by the Allegheny

Department of Health.

Dr. Roth: Dr. Jack Rozel, my guest, is an associate professor of psychiatry at the hospital and of

the University of Pittsburgh. He is the president-elect of the American Association for

Emergency Psychiatry, the leading national organization in his field. He is an

extraordinary, sought-after teacher and man of many talents and interests. Dr Rozel is

also the medical director of the resolve Crisis Services. Here, he functions at the

challenging vortex -- and by that, you need to, or should or could, imagine a Venn

diagram that overlaps. And this is where emergency and crisis psychiatry, violence

assessment and management, law, mental health, public policy, and ethics meet daily.

So that is a challenge. Congratulations, and welcome, Dr. Rozel. Perhaps we could begin

this conversation by your explaining what are resolve Crisis Services, and who are your

clients?

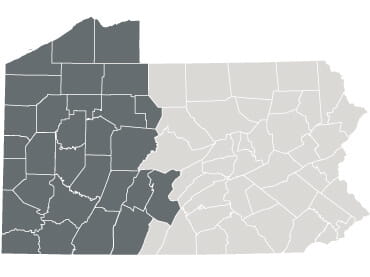

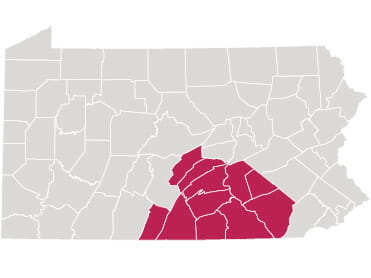

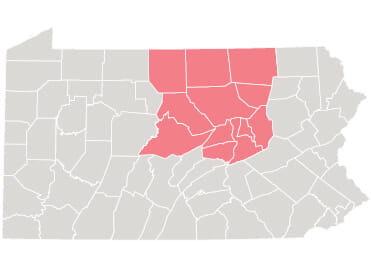

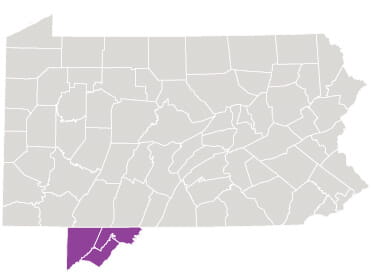

Dr. Rozel: So resolve Crisis Services have been operating here in Allegheny County now for about

10 years. We were created at a response to a request for proposals from the county. A

lot of different agencies sort of put their name in the hat, and UPMC Western

Psychiatric Hospital was chosen as the provider. What we've done is we've brought

together four core programs. I call them our core four, which is telephone crisis services,

mobile crisis services, walk-in services, and crisis residential or short-term overnight

services, all into one program. It’s sort of one team, one roof, one mission, and at the

time of inception we were built entirely around the recovery model.

Dr. Rozel: There's lots of crisis programs across our country, many of which have been developed

recently around the recovery model. But at the time we were created, to bring those

types of programs together and to do it with that recovery focus was fairly unusual, and

we provide these services 24/7, 365 all across our county. There is no charge to any

individual who reaches out for the services. It's either covered by their insurance, or it's

Transcript by Rev.com

covered by the county. It turns out that we provide somewhere between 100,000 to

125,000 services every single year to the residents of Allegheny County.

Dr. Roth: Wow. Well, that does sound quite comprehensive. So, I'm wondering: How does resolve

Crisis Services differ from most hospital emergency rooms that, for example, do see

psychiatric patients? Typically, these emergency room contacts lead to few choices, in

my experience. For example, psychiatric hospitalization or patient discharge. So what is

different, really, then, about the resolve Crisis services?

Dr. Rozel: You're absolutely right. The traditional emergency department, whether it says

psychiatric emergency service or a medical ED that's also doing psychiatric care, they

really have two, maybe three, boxes of disposition, if you will. It’s sort of vet them and

bed them -- we're going to admit this person, we want them to stay in the hospital -- or

treat them and street them. A lot of times that means we're going to give them a list of

outpatient resources. We'll tell them to call back to their other provider, but we're going

to put them back out, free-range. We're not really going to do a lot of follow-up. In

between is this issue of, we're concerned about them. We want them to have

something more than, hey, maybe you can get an outpatient appointment in blank

weeks. We want them to have a closer follow-up.

Dr. Rozel: Resolve is very much about solving the problem of that middle pathway, and we're

there for folks who are willing and voluntary and interested in engaging in treatment,

although we certainly do assist with some involuntary interventions, and we're there to

help them with whatever issue they might want help with. You don't have to come to

resolve and say I'm suicidal or I’m homicidal. You can reach out because you're tired,

you're angry, your marriage is falling apart, work is a pain, or you don't have work. It

doesn't have to be about a diagnosis. It doesn't have to be about lethality. In traditional

emergency

Dr. Roth: Let me just interrupt on one point that seems critical to me as I understand resolve, and

that is you do not have to, per se, be a psychiatric patient or have a psychiatric

diagnosis. In that sense, any person in crisis -- this is my understanding, and please

correct me if I'm wrong -- can use this unique services.

Dr. Rozel: So yeah, and as someone who's raised at the knee of diagnostic psychiatry, just down

the hall from where the DSM4-TR and DSM5 were produced, I grew up thinking a lot

about diagnosis. I went through my training thinking a lot about diagnosis. Ninety-nine

percent or more of our services are given without regards to a diagnosis. Now, that

doesn't mean some of our folks don't already have a diagnosis or may or may not meet

criteria for a diagnosis, but it doesn't have to be about the schizophrenia, the PTSD, the

depression. It can just be, “My relationship is in trouble. I don't know how to talk to

someone that's important to me about this issue.” By the way, there's nothing about

living with a psychiatric illness, severe or otherwise, that protects you from all of the

crises that we all encounter in our lives.

Dr. Roth: So there's a couple of features I'm interested in. First of all, what kinds of staff do you

have there? And then, additionally, I know you do have the services that can wrap

Transcript by Rev.com

around, that are mobile, that can go out to really help manage a problem. Perhaps you

could tell us a little bit more about that, which is really quite a wonderful capability.

Dr. Rozel: So a lot of our staffing, in some ways, comes from draft regulations that came out of

Harrisburg over 20 years ago, which, if they came out today, you’d say, wow, these are

really thoughtful and progressive. They came out of Harrisburg 20 years ago. It's, I think,

tremendously impressive. Basically, what they say is they want human services and

social services professionals who are comfortable in a crisis setting and who get the

recovery model. Now, I don't mean they have to give us a dictionary definition of

recovery; I don't know if I could do that. But they get what it's about, and they get the

idea of helping the person where they're at. And so we have a really wonderfully

eclectic mix of folks from all sorts of backgrounds. Certainly a lot of folks from

traditional mental health backgrounds, social work, dual-diagnosis, addictions,

intellectual and developmental disability, but we also have folks from child protective

services, from law enforcement. We have folks with masters in divinity degrees, and we

also have about a dozen or so certified peer specialists, which means we actually have

probably four to five times as many peer specialists working for us.

Dr. Roth: So one of the core, then, of the Crisis Services is that you have the kind of people

working there where, frankly, people in trouble can feel comfortable, as I understand it,

to talk and also to figure out in a practical sense, what might be next steps to solve their

problems. Dr. Rozel, you are known as somebody who knows how to de-escalate a

situation: a unique talent in some ways, especially valuable for our field. So I'm

wondering if you could say a little bit more about crisis resolution, conflict, deescalation, whatever you want to call it or whatever it is. What's the secret sauce here?

Dr. Rozel: As trite as it sounds, a lot of times it's as simple and as straightforward as treating

someone with dignity and respect, and I know that's a phrase that gets thrown around

easily and quickly, but it makes a profound, profound difference in how people perceive

others and how they perceive themselves as how they're being treated by others. Going

in and just respectfully saying, “Hey, I'm here to help. Help me understand what's going

on in your situation.” Not pretending that we know what's right for them, but asking

them, “What's important to you? What are your goals? What have you tried? What's

worked, what hasn't worked?” It doesn't help if I go in and say, “Oh, I think you should

do A, B, and C,” and then to have them say, “I already did A, B, and C. None of that

worked. You're an idiot.” It doesn't help anyone.

Dr. Rozel: But we begin with questions. We begin with exploration when it comes to verbal deescalation, our first-line intervention when someone might be agitated. It's this

wonderful set of skills and tools that a lot of us use in our clinical settings, across the

spectrum of behavioral and physical health. It's a lot of the same skill sets that we're

teaching to our clinicians around crisis intervention and de-escalation. It's very similar to

what we do when we think about managing acute agitation. It's what we teach to cops

and law enforcement about verbal intervention as a use-of-force alternative. It's similar

to what our risk management colleagues talk about, about how to work with an

individual or a family impacted by an adverse event in a health care setting to rebuild

that relationship.

Dr. Roth: I see. So this is far, far beyond, just to oversimplify, finding the right medication.

Dr. Rozel: Absolutely.

Dr. Roth: At core. And you are dealing with the families.

Dr. Rozel: Whenever and wherever possible, we really like to deal with the families, the natural

supports. We've worked really hard to

Dr. Roth: Some of that is outreach?

Dr. Rozel: Absolutely. Absolutely. Now, one of the challenges, by the time someone has reached

that point in their life where they're reaching out for crisis services, as much as we try to

keep that bar, that threshold for reaching out, so very low, they're coming to us, in no

small part, because they've burned their bridges. They're isolated, they're alone, and the

family, the primary supports who may have been there for them six months or six years

ago, aren't there for them anymore. That's why they're reaching out to us today. But

certainly whenever they're involved, we want to get them involved because they're so

important in that person's recovery and just helping us understand how are they doing,

how do they look today versus how do they look a week ago or a month ago or a year

ago.

Dr. Roth: So I'd like to change the subject just a little bit, but it is clearly a related subject, given

the kinds of crises that you do deal with. That is, Dr. Rozel, you're also known as a

person who has a great expertise when one hears a threat. That threat could be to harm

another, that threat could be the possession of a weapon, even. This is your area. So I

would like you to talk a little bit more about that. I am a clinician, and I have a patient

who may be, at least potentially, homicidal, or I'm fearful of that, or suicidal. What is it

that you bring to that situation?

Dr. Rozel: So one of the first things I'll say is most of the really good research that's out there says

that most of the violence we see in our community, both regionally and across the

country, has little, if anything, to do with mental health, psychiatric illness, psychiatric

diagnoses. If we snapped our fingers and all the psychiatric illness that's out there just

resolves itself as we're sitting here chatting, we still have something like 90 to 95

percent of the violence that's out there. Now, most people with a psychiatric illness are

not violent. Most of the violence is not attributable to mental illness, but there is an

intersection. It's small. It's significant. It's important to manage properly. When we

approach a threat situation where someone has made a comment or a statement,

there's a lot of different layers that we look at.

Dr. Rozel: One of the first things is, was this a transient threat, or is this a sustained intended

threat? Lots of people get frustrated and get angry and make an off-the-cuff statement

because they're frustrated or they're pissed off. In the heat of the moment, maybe they

mean it or maybe they're just annoyed and they want to poke back and they'll say, “This

is how mad I am.” We absolutely want to reach out to those folks, help them, provide

them with maybe some better stress response skills. We want to look at them, make

Transcript by Rev.com

sure that there's not something else going on, but the people that we're really

interested in from a safety and security perspective are the people who will hold that

idea, who hold that grudge and say, “You know what? Now I really am serious about

this.” Sometimes these are folks who may just be misunderstood and they'd said

something that was really benign that was overinterpreted as a threat.

Dr. Rozel: Sometimes we see people that they were trolling, they were hoaxing, they're trying to

get that rise. Sometimes we see that transient anger: They flare up and then they calm

down, the hotheads. But the ones we're really interested in monitoring and working

with are the ones that say, “You know what? No, these people have wronged me. They

wronged me over and over again. They've hurt me, and now I'm going to hurt some

people back.” They don't do it out of a sense of, “I'm a bad person.” They do it because

the world has treated me unfairly. The world is unjust and now I figured out a way to fix

it.

Dr. Roth: So you have a certain format about trying to evaluate these threats in terms of their

seriousness or whether interventions are necessary. I happened to read one of your

recent papers that you wrote with Dr. Solomon and Dr. Jane, and I noticed in there that

you had developed a set of general questions about firearms and weapons. Do you

think, for purpose of illustration, you could give us some of those really important

questions to ask?

Dr. Rozel: So, absolutely. I think any time we're concerned about a safety issue, whether it's

aggression or violence, whether it's suicidality, whether it's accidental injury, it is

absolutely appropriate and OK for health professionals to ask about firearm access and

to provide guidance about safer storage. So I'm clear, not safe storage, but safer storage

or removal. Much in the same way our reproductive health colleagues talk about safer

sex, not safe sex, we talk about safer storage. As a simple mnemonic to start off with,

we think about A-E-I-O-U. So A: access. How hard is it for you to access a gun, or do you

have access to a gun at home? Some people will say, “I'm really upset. I don't have a

gun.” Well, if you needed a gun, how would you get it? “I have no idea. Do I have to go

to a store, do I have to do fingerprints?” Or, “Oh yeah, just go to my cousin Eddie and

he'll give me the gun.” Or, “I just go to so-and-so down the street, I'll get a gun.”

Dr. Rozel: So, that's the first: access. Do you have access, or how hard is it for you to access? E:

experience. Have you ever used a gun before? OK, you've got a gun, but it's Uncle

Monty's hunting rifle that was inherited seven years ago. It's collecting dust in the

closet. Or, this is my ceramic-coated, blah blah, blah, this model nine-millimeter with

these sights. How much experience? Have they used it on a range? Are they law

enforcement or a veteran of the military, where they've had the lived experience of

using a gun to keep themselves or others safe and they know how to use it effectively?

Dr. Roth: Well, I can remember I-O-U, so what are those three ideas?

Dr. Rozel: So ideation or intent: Are they actually thinking about using that firearm in a dangerous

or harmful way? Lots of people own guns. That doesn't mean that they're inherently

dangerous. We don't want to marginalize 40 to 45 percent of our society just because

they happen to be gun owners. But are they actually thinking about using it in a

Transcript by Rev.com

dangerous way? O: operational plan. I had a patient many years ago who had one of

those “Family Circus” house maps with the little dotted line that was started off with

Dad's gun cabinet, Mom and Dad's room, sister's room. Then he had another map for

the school, principal, counselors. So, yeah, there was a specific plan of how they were

going to use it. U is unconcerned with consequences. Hopelessness, suicidality. Lots of

folks may have fleeting thoughts about, “Oh, I'm mad at so-and-so, I'm going to go after

them, but I wouldn't do it because I don't want to get arrested, it's morally wrong,” or

something else.

Dr. Rozel: But if I've given up on my future and my life, if I'm feeling suicidal, if I'm suddenly

thinking about being terminally ill, then some of those barriers have eroded

significantly, and so we get a lot more concerned about their risk then.

Dr. Roth: A-E-I-O-U. Well, I can remember that then. I think you've given us some good tips. You

are working in an area where not every person feels up to it, to put it bluntly, and can

even be a bit frightening. So I wonder if you could then, in closing, tell us a little bit more

about your career evolution. How did you come to be interested in such demanding and

evolving topics?

Dr. Rozel: Well, one of my colleagues made the comment, “Weed well in dark places so you don't

have to.” The interest in violence, the interest in emergency settings, part of it is, I think

it's intrinsically interesting material. It's at the nexus of some of the most acutely ill,

some of the most resource-challenged people in communities and environments. It

draws in clinical need, community benefit, tremendous questions about ethics and law,

some of which are easily resolved if you just know the law, the court ruling, and you can

point your finger at it. But a lot of it, you're just left scratching your head because, yeah,

this doesn't really fit in any of these patterns.

Dr. Roth: When you were 16 or 17 years old, did these questions ever occur to you? Or how did it

come that here we are having this discussion today?

Dr. Rozel: Well, I did an EMT training when I was in high school, and I spent some time hanging on

the back of the ambulance, as they say, and hanging out in the ERs, and I hit college

thinking, I want to do emergency medicine or intensive care.

Dr. Rozel: I ended up volunteering at a Samaritan's hotline, a suicide hotline in Rhode Island, that

was near a college campus and was awe-struck, that in 10-

Dr. Roth: This is in high school?

Dr. Rozel: No, this was actually in college, I was a volunteer at the hotline. To sit on the phone with

someone for 15 minutes and say not much more articulate than “Mm-hmm, tell me

about that,” and to make a difference in someone's life, it was captivating. I remember

thinking, imagine if I actually knew what to do more than just sitting there and listening,

and here I am, more than 25 years later, realizing that just being present and in the

moment and listening and letting someone tell their story is the most important part of

just about every interaction we have.

Dr. Roth: Well, I think residents in my training and educational interactions say, well, how did

your career develop? I think you're an example of what is often the case, namely what

really interests you. It turns out that some volunteer job or something that you wanted

to do to make a difference or something that you just got so interested in has maybe a

lot more to do with it in that career choice than, for example, all that you've learned in

school.

Dr. Rozel: A lot of good luck and happenstance exposures, a lot of wonderful mentors and

colleagues to sort of nudge me and prod me and guide me along the way.

Dr. Roth: OK. Well, I think you've told us a lot about Crisis Services and the extensive, but needed,

kinds of services to resolve crises, and then of your own interest in special expertise in

this area. We very much appreciate talking with you today, and best of luck to you.

Dr. Rozel: Thank you.

Dr. Roth: Now, in closing, I'll simply note that this podcast, as well as some key references to the

kinds of writings and advice that Dr. Rozel and his colleagues have given, will all shortly

be on the UPMC website itself under the designation “UPMC Western Psychiatric

Hospital.” You can relisten or read more. Also in our Department of Psychiatry website,

where we do feature our faculty and their achievements. Thank you, Dr Rozel.

Dr. Rozel: Thank you.