Lindsey caught the concern. Heard the questions. Noted the doubts.

A serious foot injury Lindsey suffered on a routine soccer play led many to wonder if she would ever lace up her cleats again. That included coaches, teammates, friends, and even her own mother, who suggested Lindsey give up the game.

Rather than heed those thoughts, Lindsey went the other way.

“As a player for the game you love, that makes you angry,” Lindsey says. “Hearing that as a young athlete, and I mean, a pretty good athlete, that was just unacceptable to me. It wasn’t an option.”

Lindsey turned those doubts into determination to get back to playing soccer. She wouldn’t give up until she got back on the field.

"My athletic trainer and I came up with a motto, and it was, ‘No surrender.’ And whenever I was frustrated, whenever I didn’t want to do an exercise or workout, she would make sure to send me a text. And it would say: ‘No surrender." — Lindsey

‘I Went into Shock Right Away’

It happened on a move Lindsey executed many times throughout her soccer career. A sophomore forward at Shaler Area High School in October 2016, she collected the ball from a punt and turned. But while the rest of her body moved, her left foot stayed in place.

“It instantly tore everything,” Lindsey says. “Then I went into shock right away.”

At the time Lindsey didn’t even know the name of the injury she’d just suffered: a Lisfranc injury.

Lisfranc injuries occur either with the breaking of bones in the midfoot or the tearing of ligaments that support the midfoot. They can be mistaken for a sprain, but Lisfranc injuries are severe and can require surgery and months of recovery. If not diagnosed properly, Lisfranc injuries can lead to long-term disability.

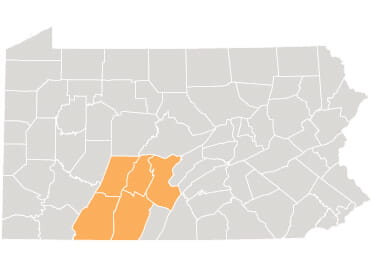

“These are often either underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed, or the severity of the injury is not initially appreciated,” says MaCalus Hogan, MD, an orthopaedic foot and ankle surgeon at UPMC. “And in Lindsey’s particular case, she had a great athletic trainer and team taking care of her. They were really concerned about her injury from the onset.”

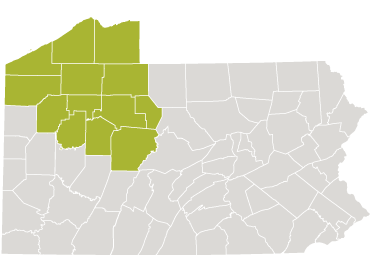

Donna Rife, LAT, ATC, an athletic trainer for UPMC Sports Medicine who works with Shaler’s athletes, suspected a Lisfranc injury almost immediately.

“I knew we were in trouble,” says Rife, who adds that Lindsey attempted to walk off the field under her own power but couldn’t make it the whole way. “I was hoping by the time she got to me that it was a high ankle sprain because those heal in about four to six weeks. I knew the Lisfranc injury, 99 percent of the time, it’s surgical. It’s something that soccer players traditionally have a hard time coming back from.”

The severity was clear right away for Lindsey’s parents, who watched their daughter battle other injuries over the years.

“That was one of those nights where I could tell she wasn’t going back in to play,” says Greg, Lindsey’s father. “She was down, and she looked at me, and I could kind of tell. And then I immediately went on the field, which you’re really not supposed to, but I just knew it was serious enough.”

The game never stopped, but Rife helped Lindsey off the field and took her to the bench for an evaluation.

“The athletic trainer removed my shoe, but I was kind of nervous because I thought it was going to look deformed because that’s what it felt like,” she says. “So, she got it off. It wasn’t deformed; it was just very swollen.”

Rife told Lindsey’s family that she suspected a Lisfranc injury, and they went to the emergency department that night. They visited Dr. Hogan the next day, and he said he also suspected a Lisfranc injury.

An MRI after the swelling went down made the diagnosis official.

That was one bombshell. Then came another, when Dr. Hogan said Lindsey would need surgery, followed by months of rehabilitation.

“Once we heard the process and the length of recovery, I don’t know, it was devastating,” says Diana, Lindsey’s mother.

‘No Surrender’

Lindsey needed two surgeries. In the first, Dr. Hogan installed a plate and five screws to repair the damage. In the second, months later, he removed them.

“As an orthopaedic surgeon approaching the foot and the ankle, the goal is really to get people back moving,” Dr. Hogan says. “And as I look at it, the foot and the ankle, it’s essentially the foundation of our gait, our mobility, our ability to move.

“And regardless of whether it’s an athlete or elderly patient who just really wants to enjoy their daily activities and walking with their loved one … you have to take an individualistic approach and a personalized approach with all the patients.”

Lindsey wanted to do more than just move normally again: She wanted to return to the soccer field. She aspired to become a Division I player growing up, and she didn’t want to end her career with an injury.

“A lot of people that sustain the (Lisfranc) injury don’t come back from it, so that was another reason why I knew that I had to try my best to come back,” Lindsey says.

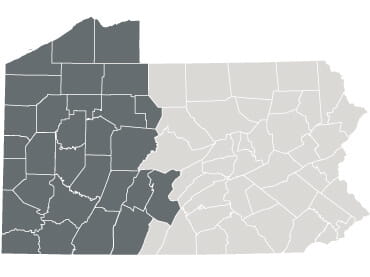

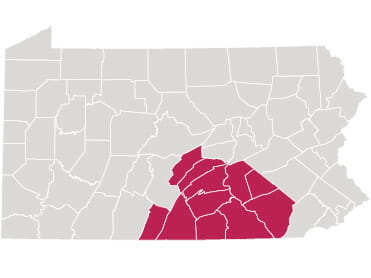

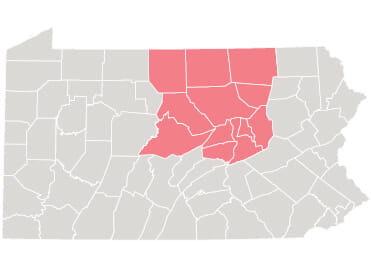

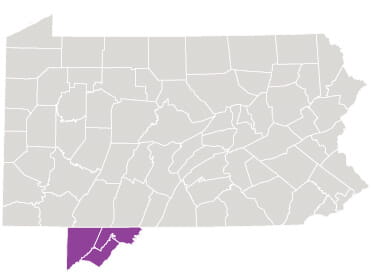

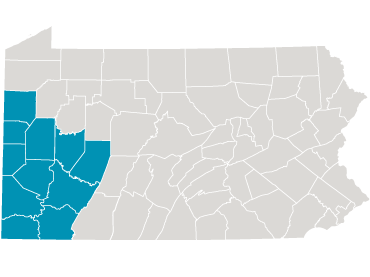

Lindsey was on crutches for more than three months, unable to put weight on her foot. But she pressed still through her rehab: at UPMC Lemieux Sport Complex, UPMC Rooney Sports Complex, and at school.

“It was amazing being able to come back from something so devastating,” she says. “And I had so many people next to me motivating me, pushing me. My athletic trainer and I came up with a motto, and it was, ‘No surrender.’ And whenever I was frustrated, whenever I didn’t want to do an exercise or workout, she would make sure to send me a text. And it would say: ‘No surrender.’

“And I just kind of lived by that.”

Lindsey made incremental improvements, setting attainable goals and getting better each day. She stayed at school two hours after classes ended each day to work out with Rife. At first, with Lindsey unable to put weight on her foot, the rehab consisted of exercises she could do, such as leg raises or arm workouts. Eventually Lindsey started running in the pool.

“I don’t want to say she made it look easy because it certainly wasn’t easy, but she was so diligent with it and worked through it,” Greg says.

After the second surgery removed the plate and screws, Lindsey spent two more weeks on crutches. It took about four to six weeks before she could run again. By early April, six months to the day of her injury, she was jogging. And by her junior year at Shaler, she was right where she expected to be: on the soccer field.

“There’s a lot of people that don’t come back from that type of an injury,” Rife says. “They just hang up the cleats and say, ‘No, I can’t do this.’ I’ve had that more than once. Or, ‘I’m in too much pain – I can’t get through this.’”

‘I Want to be an Inspiration’

Lindsey doesn’t consider herself an emotional person. But talking about her injury, even now, can cause her to tear up.

“It’s just a very hard subject for me,” she says. “And not everybody knows exactly what I went through, and I think that’s hard for them to understand where I’m coming from and for me because it was so difficult. But if you don’t go through something, you don’t know how to handle it.”

But she’s turning her soccer setback into a positive. She learned from her injury how much she enjoyed helping people.

“I think she had a little bit of an interest (before her injury) but wasn’t really sure what she wanted to do, and I think this has really piqued her interest,” Rife says.

Lindsey worked in the medical tent at the DICK’S Sporting Goods Pittsburgh Marathon and the UPMC Health Plan Pittsburgh Half Marathon in May 2018 and 2019. She helped runners who needed assistance. She helped Rife out in Shaler’s athletic training room during the winter of her junior year.

She also answers others’ questions about Lisfranc injuries: from a teacher whose daughter suffered the injury, to people who reach out over social media.

“I just really enjoy being there for people, and I want to be an inspiration to others to get back to what they love doing,” Lindsey says.

Lindsey attends Penn State University; while she doesn’t play Division I soccer for the Nittany Lions, she does play recreationally. But that’s only part of her story: She plans to become a physical therapist or something else in the medical field.

“She made something that could have been completely devastating to a 16-year-old high school kid into something that will motivate her and propel her into the future,” Diana said. “I have no doubt that she would be one of the best physical therapists that anyone could want.”